- Home

- Services

- Hi-Line Engineering

- About

- Careers

- Contact

- Requests For Proposals

Survey Says!

by GDS Associates, Inc | December 14, 2021 | Other Specialized Services , Newsletter - TransActions

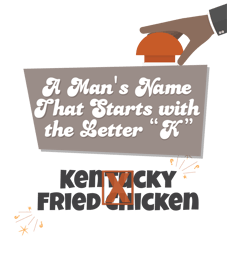

I love game shows. I fondly recall those days when I would be sick and get to stay home from school and at 11:00 AM, The Price is Right with Bob Barker would start. It was fun to play along and see if I could have won that new car. Every evening as a teen, my family would watch Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy. I remember back to the days when the contestants had to purchase prizes with price tags on them from a showcase after winning a round in Wheel of Fortune. Those were the three games shows I have watched the most, but one more worth mentioning is implied by the title of this article. The gist was, they had supposedly gone out and surveyed 100 Americans about a variety of topics, and families would “feud” over trying to guess the most popular answers. The format is simple and allows for easy play from home, which is probably why Family Feud is a legacy game show with a long history. The final round, in which contestants must try to pick answers for the category and are on the clock, creates a level of pressure that can lead to some really whacky answers. Even before the days of memes and social media, I recall an email of funny and embarrassing answers provided in the final rounds of Family Feud. I’ve thrown in some of my favorites throughout this article.

I love game shows. I fondly recall those days when I would be sick and get to stay home from school and at 11:00 AM, The Price is Right with Bob Barker would start. It was fun to play along and see if I could have won that new car. Every evening as a teen, my family would watch Wheel of Fortune and Jeopardy. I remember back to the days when the contestants had to purchase prizes with price tags on them from a showcase after winning a round in Wheel of Fortune. Those were the three games shows I have watched the most, but one more worth mentioning is implied by the title of this article. The gist was, they had supposedly gone out and surveyed 100 Americans about a variety of topics, and families would “feud” over trying to guess the most popular answers. The format is simple and allows for easy play from home, which is probably why Family Feud is a legacy game show with a long history. The final round, in which contestants must try to pick answers for the category and are on the clock, creates a level of pressure that can lead to some really whacky answers. Even before the days of memes and social media, I recall an email of funny and embarrassing answers provided in the final rounds of Family Feud. I’ve thrown in some of my favorites throughout this article.

Talk of a silly game show leads to a good question about surveying methodology. Namely, could we consider a survey of 100 Americans to be a fair representation of America at large? This question, although focused on a game show, is relevant today for many reasons. Consider political poling, which has seemed to have gotten worse in predicting election outcomes in recent decades. Surveying can be a powerful tool for a manager (whether a campaign manager or a manager of an electric/water/gas utility), but surveys are statistical tools that must be used correctly. If I try to loosen a half-inch bolt using the wrong sized socket, I may not accomplish that for which I set out to accomplish. Likewise, in an internet age when conducting a survey has become relatively easy, if I use the tool incorrectly, I may not accomplish my objective.

which has seemed to have gotten worse in predicting election outcomes in recent decades. Surveying can be a powerful tool for a manager (whether a campaign manager or a manager of an electric/water/gas utility), but surveys are statistical tools that must be used correctly. If I try to loosen a half-inch bolt using the wrong sized socket, I may not accomplish that for which I set out to accomplish. Likewise, in an internet age when conducting a survey has become relatively easy, if I use the tool incorrectly, I may not accomplish my objective.

Even though many utilities do not compete for their customer

base, it can be very useful to understand their customer base,

their attitudes toward energy consumption, their use of energy

consuming equipment in the home, or their awareness and

understanding of utility programs. Sure, a utility carefully

designed a program that is to the benefit of their retail

customers and the utility, and then promoted it through a bill

insert and in a couple of public forums. But what good is that

program if only a few of the customers know about it? A survey

can help answer that question. Think about it for a moment: is

asking 100 customers a fair representation of your entire

customer base? If not, how many do you think you need to

survey to gain representative information?

It turns out there are several major elements to determining the

appropriate sample size. I’ll touch on each briefly, without using

a single math equation.

WHAT ARE YOU MEASURING?

The first key point to establishing a good survey sample

size is to identify what is being measured with the survey. There

are two types of information we are interested in measuring. The first is knowing what percentage of the population responds in a certain way. This is the Family Feud model, in which we are

asking, what percentage of Americans say “car” when asked,

“Name something with wheels”. The second type of

measurement is the value of a continuous variable. For instance,

trying to measure the peak demand for a typical home in a

service territory. The necessary statistical formulas are different

for determining the appropriate sample size.

HOW CONFIDENT DO YOU WANT TO BE?

It’s hard to escape the concept of confidence when doing statistical experiments. It’s natural to want to draw one sample (run a single survey) and make inferences about the entire population from that single sample. The level of confidence in the survey results is established at the outset and has an impact on sample size. Confidence levels typically range from 85% to 99%, and the greater the confidence desired, the larger the sample size will be. Think of the confidence level as the ability to do the exact same survey many times and how often the survey answer would fall within a certain bandwidth. If the answer needs to fall within the bandwidth 99% of the time, then the survey needs a larger sample size. For many utility surveys, 90% or 95% confidence is typically desired.

sample size will be. Think of the confidence level as the ability to do the exact same survey many times and how often the survey answer would fall within a certain bandwidth. If the answer needs to fall within the bandwidth 99% of the time, then the survey needs a larger sample size. For many utility surveys, 90% or 95% confidence is typically desired.

HOW PRECISE DO YOU WANT TO BE?

The level of precision is reported after the survey has been conducted and is often reported as the margin of error. The precision determines how narrow the margin of error is. When designing a survey sample size, it’s necessary to assume a targeted level of precision, usually 5% or 10%. Once the survey

is conducted, though, the actual precision will be measured when summarizing responses. Initially, the survey may have a

targeted precision of +/- 10%, but enough survey responses are

received that the precision is +/- 6%. The more precise the survey needs to be, the larger the sample size of the survey.

POPULATION SIZE

Another key factor is the size of the population we are trying to represent in the survey. For a political poll, pollsters are trying to represent the full population of voters. An extremely challenging population to pin down since voter turnout is difficult to predict. For a utility, things get a little easier because the utility already knows the number of retail customers on its system. The smaller the population, the lower the sample size needs to be to draw the same level of precision and with the same confidence.

BEER BREAK

We have touched on the major factors that impact sample size and it has made me thirsty. Well, one of the other major factors in sample size calculations is attributable to one tasty beverage – beer. Back in the early 1900s, a gentleman by the name of William Sealy Gosset was working for Guinness Brewing and was researching barley recipes. He was trying to draw conclusions from small sample sizes and ended up developing a mathematical approach based on a new probability distribution he created. In those days, corporations did not want their employees named in academic publications, so Mr. Gosset published a paper about his work in Biometrika in 1908. He wrote under the pseudonym “Student” and to this day we make use of a statistical distribution known as Student’s t-distribution. The t-distribution is what translates the confidence level into a sample size – so raise a glass in honor of yet another contribution to society from beer!

– beer. Back in the early 1900s, a gentleman by the name of William Sealy Gosset was working for Guinness Brewing and was researching barley recipes. He was trying to draw conclusions from small sample sizes and ended up developing a mathematical approach based on a new probability distribution he created. In those days, corporations did not want their employees named in academic publications, so Mr. Gosset published a paper about his work in Biometrika in 1908. He wrote under the pseudonym “Student” and to this day we make use of a statistical distribution known as Student’s t-distribution. The t-distribution is what translates the confidence level into a sample size – so raise a glass in honor of yet another contribution to society from beer!

SO, IS 100 RESPONSES ENOUGH?

The answer, it turns out, is maybe. For example, a survey needs 68 responses from a very large population to achieve a 90% confidence and +/- 10% precision. But to get more precision requires more responses, for example, a 95% confidence and +/-5% precision level requires just under 400 responses.

Just as important as the sample size is ensuring the sample is

truly representative of the population of interest. This is the part

political pollsters try very hard to accurately capture, by trying to

poll likely voters with an appropriate mix of political persuasions. Errors in the representation of their polls will lead to big variations between election day results and their polls.

Likewise, if the utility only receives responses from a certain segment of their customers, then it may interpret the results incorrectly. Therefore, survey design should also carefully consider the representative nature of the sample drawn.

That’s probably more information about sample size than anyone other than an ardent stats nerd or quant would want to

know. The point is surveying is easy and I encourage utilities to

take advantage of seeking information about their customers.

With internet and email, it can be simple to run a survey and

collect information that can be useful for various planning efforts, including developing load forecasts, fine tuning utility

programs, or just understanding customer attitudes about the

utility. However, easy execution of a survey should be balanced

with using the tools correctly to avoid making the mistake of

drawing incorrect inferences from survey data collected.

For more information or to comment on this article, please contact: Jacob Thomas, Principal

Jacob Thomas, Principal

GDS Associates, Inc.

Marietta, GA

770-799-2381 or

jacob.thomas@gdsassociates.com

GET OUR NEWSLETTER

RECENT POSTS

- Protect the Grid: Act on Facility Ratings Today

- Why MOD-026-2 Matters: Raising the Bar for Generator and IBR Modeling Reliability

- Exploring the 2026-2028 Reliability Standards Development Plan

- Blackstart Resource Availability During Extreme Cold Weather Conditions

- DOE Pushes FERC to Accelerate Large Load Grid Access

Archives

- December 2015 (8)

- June 2025 (7)

- January 2016 (6)

- July 2016 (6)

- March 2021 (6)

- May 2022 (6)

- August 2020 (5)

- March 2015 (4)

- January 2019 (4)

- June 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (4)

- February 2020 (4)

- May 2020 (4)

- June 2020 (4)

- December 2020 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- October 2021 (4)

- April 2024 (4)

- December 2024 (4)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2015 (3)

- August 2016 (3)

- February 2017 (3)

- July 2017 (3)

- February 2018 (3)

- February 2019 (3)

- November 2019 (3)

- March 2020 (3)

- April 2020 (3)

- September 2021 (3)

- December 2021 (3)

- August 2022 (3)

- December 2022 (3)

- April 2023 (3)

- July 2023 (3)

- December 2023 (3)

- September 2024 (3)

- October 2025 (3)

- December 2025 (3)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2016 (2)

- March 2016 (2)

- September 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- January 2017 (2)

- July 2018 (2)

- November 2018 (2)

- March 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (2)

- July 2020 (2)

- September 2020 (2)

- April 2021 (2)

- August 2021 (2)

- October 2024 (2)

- September 2025 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- April 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- August 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- February 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (1)

- October 2016 (1)

- December 2016 (1)

- October 2018 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (1)

- October 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- April 2022 (1)

- July 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- August 2023 (1)

- October 2023 (1)

- July 2025 (1)

- November 2025 (1)

- January 2026 (1)

Categories

- Newsletter - TransActions (85)

- News (78)

- Employee Spotlight (35)

- Energy Use & Efficiency (28)

- Energy, Reliability, and Security (18)

- Other Specialized Services (11)

- Environment & Safety (10)

- Power Supply (8)

- Transmission (8)

- NERC (7)

- Utility Rates (7)

- Cyber Security (5)

- Energy Supply (4)

- Hi-Line: Utility Distribution Services (4)

- Battery Energy Storage (3)

- Uncategorized (2)

- Agriculture (1)

- Hi-Line: Seminars & Testing (1)