- Home

- Services

- Hi-Line Engineering

- About

- Careers

- Contact

- Requests For Proposals

Disinfectant Contact Time is Not Zero!

by GDS Associates, Inc | June 11, 2020 | Other Specialized Services , Environment & Safety

“Contact time,” as used by the EPA, is “the amount of time the surface should be treated for. The surface should be visibly wet for the duration of the contact time.” In practice, most people spray the countertop or others surface, wipe it off and go about their business, assuming that pathogens (aka germs) are killed on contact. It will come as a surprise to many that disinfectants simply do not work this way, and that EPA contact time is measured in minutes.

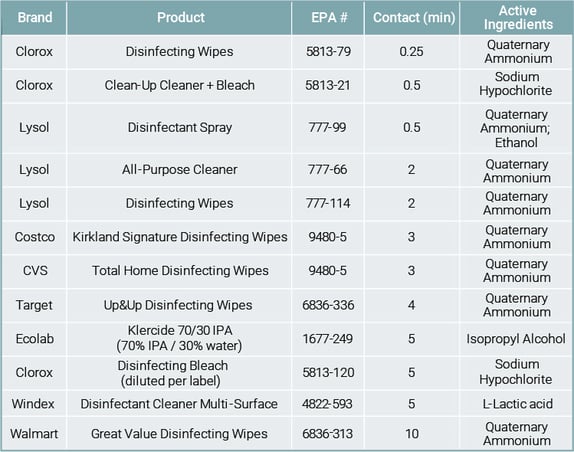

Disinfectants are “antimicrobial pesticides” regulated and defined by the EPA as “substances or mixtures of substances used to destroy or suppress the growth of harmful microorganisms such as bacteria,viruses, or fungi on inanimate objects and surfaces” as opposed to hand sanitizers, which are regulated by the FDA and intended only for use on skin. Any legally marketed disinfectant will display an EPA registration number on the product label that allows the user to access all related product information, including the required contact time, on the EPA pesticide registration website. “List N” identifies products registered for use against SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, our current pandemic affliction. This has direct implications for the spread of virus, since common practice does not reflect the need to keep the target surface wet for up to 10 minutes before contact. How many of us watch grocery cart handles being wiped or sprayed by store personnel and then offered for use with a total contact time of around five seconds?

If enforced, disinfectant contact time becomes a major chokepoint for venues that rely on frequent passthrough of riders or passengers (think amusement parks) while trying to do rapid wipe-downs or sprays between runs. Long-contact products will put the brakes on that.

The math also looks bad for voters, since the touch screens, knobs and other contact points on voting machines will require disinfection and a contact-time delay before the next voter steps up. Added to the already complicated logistics of long lines, social distancing and limited voting hours and stations, it is difficult to imagine tens of thousands of precinct personnel across the nation having the necessary and approved disinfectants and supplies and successfully enforcing both the cleaning and timing for every voter at every station.

There are thousands of disinfectants in the marketplace, and this list is not intended to promote or demote any of them. It is meant only to demonstrate the range of contact times and inform readers to consider contact time when selecting a product. Finding that number is usually not as simple as it should be, since labels tend to shout “Kills 99.9% of germs*” while burying contact time (if there at all) in very small print in the use instructions. The takeaway here is that disinfectants do not kill on contact, treated surfaces should not be considered “clean” until the prescribed contact time has expired, and that faster is better for most users. To borrow from a familiar idiom, it ain’t over until the disinfectant disrupts the viral outer lipid bilayer and disables its nucleocapsid proteins — and that takes time.

There are thousands of disinfectants in the marketplace, and this list is not intended to promote or demote any of them. It is meant only to demonstrate the range of contact times and inform readers to consider contact time when selecting a product. Finding that number is usually not as simple as it should be, since labels tend to shout “Kills 99.9% of germs*” while burying contact time (if there at all) in very small print in the use instructions. The takeaway here is that disinfectants do not kill on contact, treated surfaces should not be considered “clean” until the prescribed contact time has expired, and that faster is better for most users. To borrow from a familiar idiom, it ain’t over until the disinfectant disrupts the viral outer lipid bilayer and disables its nucleocapsid proteins — and that takes time.

About the Author:

About the Author:

Scott Harris, PhD is the Associate Director of EHS Services in the Austin, TX office of GDS Associates, Inc. and an adjunct faculty at University of Texas at San Antonio, University of Utah and UNC-Chapel Hill. Dr. Harris received his PhD in Environmental Science, with a specialization in Disaster and Emergency Management, from Oklahoma State University and holds degrees in Public Health and Geology from Western Kentucky University.

Scott Harris, PhD | CONTACT

512-717-8053 or scott.harris@gdsassociates.com

GET OUR NEWSLETTER

RECENT POSTS

- Protect the Grid: Act on Facility Ratings Today

- Why MOD-026-2 Matters: Raising the Bar for Generator and IBR Modeling Reliability

- Exploring the 2026-2028 Reliability Standards Development Plan

- Blackstart Resource Availability During Extreme Cold Weather Conditions

- DOE Pushes FERC to Accelerate Large Load Grid Access

Archives

- December 2015 (8)

- June 2025 (7)

- January 2016 (6)

- July 2016 (6)

- March 2021 (6)

- May 2022 (6)

- August 2020 (5)

- March 2015 (4)

- January 2019 (4)

- June 2019 (4)

- August 2019 (4)

- February 2020 (4)

- May 2020 (4)

- June 2020 (4)

- December 2020 (4)

- July 2021 (4)

- October 2021 (4)

- April 2024 (4)

- December 2024 (4)

- May 2025 (4)

- April 2015 (3)

- August 2016 (3)

- February 2017 (3)

- July 2017 (3)

- February 2018 (3)

- February 2019 (3)

- November 2019 (3)

- March 2020 (3)

- April 2020 (3)

- September 2021 (3)

- December 2021 (3)

- August 2022 (3)

- December 2022 (3)

- April 2023 (3)

- July 2023 (3)

- December 2023 (3)

- September 2024 (3)

- October 2025 (3)

- December 2025 (3)

- May 2014 (2)

- February 2016 (2)

- March 2016 (2)

- September 2016 (2)

- November 2016 (2)

- January 2017 (2)

- July 2018 (2)

- November 2018 (2)

- March 2019 (2)

- May 2019 (2)

- July 2020 (2)

- September 2020 (2)

- April 2021 (2)

- August 2021 (2)

- October 2024 (2)

- September 2025 (2)

- February 2014 (1)

- April 2014 (1)

- July 2014 (1)

- August 2014 (1)

- November 2014 (1)

- February 2015 (1)

- May 2015 (1)

- June 2015 (1)

- November 2015 (1)

- October 2016 (1)

- December 2016 (1)

- October 2018 (1)

- December 2018 (1)

- April 2019 (1)

- July 2019 (1)

- September 2019 (1)

- October 2020 (1)

- November 2020 (1)

- February 2021 (1)

- April 2022 (1)

- July 2022 (1)

- October 2022 (1)

- August 2023 (1)

- October 2023 (1)

- July 2025 (1)

- November 2025 (1)

- January 2026 (1)

Categories

- Newsletter - TransActions (85)

- News (78)

- Employee Spotlight (35)

- Energy Use & Efficiency (28)

- Energy, Reliability, and Security (18)

- Other Specialized Services (11)

- Environment & Safety (10)

- Power Supply (8)

- Transmission (8)

- NERC (7)

- Utility Rates (7)

- Cyber Security (5)

- Energy Supply (4)

- Hi-Line: Utility Distribution Services (4)

- Battery Energy Storage (3)

- Uncategorized (2)

- Agriculture (1)

- Hi-Line: Seminars & Testing (1)